The Supreme Court vacated and remanded Tuesday an appeals court decision that found under federal common law, a tax refund due from a joint tax return generally belongs to the company responsible for the losses that form the basis of the refund, rejecting a nearly half-century-old precedent.

In Rodriguez v. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the case involved the issue of whether a parent corporation or its subsidiary owns a tax refund during bankruptcy proceedings.

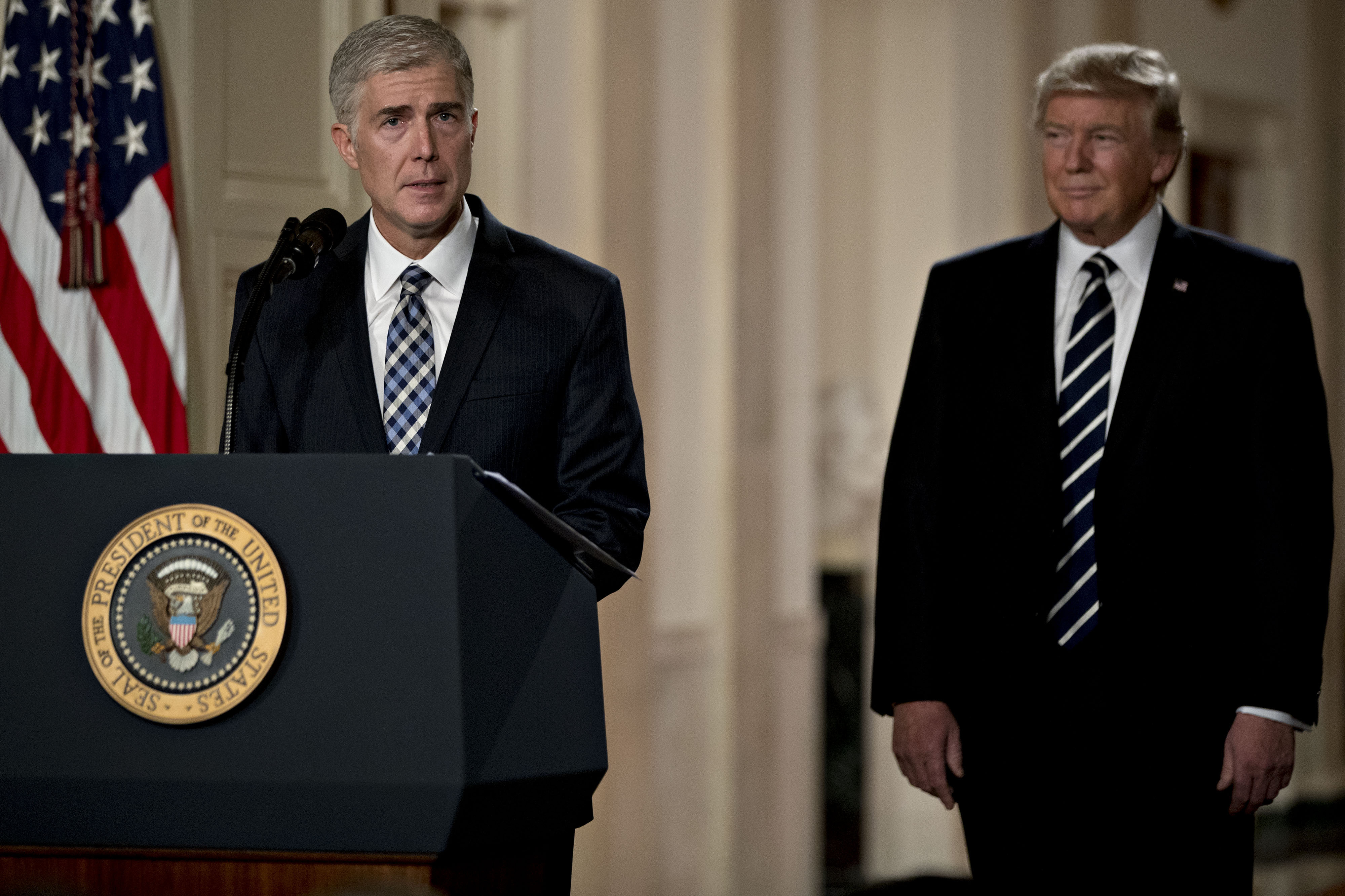

Justice Neil Gorsuch (pictured with President Trump), in his opinion, explained the facts of the case: “The trouble here started when the United Western Bank hit hard times, entered receivership, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation took the reins. Not long after that, the bank’s parent, United Western Bancorp, Inc., faced its own problems and was forced into bankruptcy, led now by a trustee, Simon Rodriguez. When the Internal Revenue Service issued a $4 million tax refund, each of these newly assigned caretakers understandably sought to claim the money. Unable to resolve their differences, they took the matter to court.”

The bankruptcy court agreed with Rodriguez, the FDIC appealed the ruling, and the district court reversed. The Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the district court, ruling for the FDIC as receiver for the subsidiary bank rather than for Rodriguez as trustee for the corporate parent.

In reaching its decision, the Tenth Circuit applied federal common law under the Bob Richards rule, which provided that, in the absence of an agreement, a refund belongs to the group member responsible for the losses that led to it. In this case, there was an allocation agreement, but the Tenth Circuit applied a more expansive version of the rule, applying it even to situations where there is an agreement unless the agreement unambiguously specifies a different result. The Supreme Court held that the Bob Richards rule is not a legitimate exercise of federal common lawmaking, and vacated and remanded the decision. “Whether this case might yield the same or a different result without Bob Richards is a matter the court of appeals may consider on remand,” Gorsuch stated.

Some tax experts see the case as a significant reversal from previous rulings. “I was surprised that the Supreme Court has thrown out the Bob Richards doctrine, since it has been used by most courts as a factor in cases over the last 47 years,” said Lee Zimet, senior director with Alvarez Marsal Taxand LLC. “Only the courts in the Sixth Circuit have refused to apply federal common law. The elimination of the use of federal common law in deciding ownership of tax refund cases will make the case decisions less predictable. Without the application of Bob Richards, the cases will be decided solely based upon the nuances of state corporate law and the specific language of a tax sharing agreement.”

In the Rodriguez case, the Supreme Court reaffirmed the application of state law to determine property rights in a bankruptcy case, even when the property in question is a federal tax refund, according to Annette Jarvis, a partner in the international law firm Dorsey Whitney.

“The Supreme Court overturned federal court-created federal common law that had existed in many Circuits for over 45 years and, in so doing, severely limited the ability of federal courts to create federal common law,” she said. “Restricting federal court common lawmaking to that which is ‘necessary to protect uniquely federal interests,’ the Supreme Court found this narrow ability to create common law not to apply to the allocation of federal tax refunds even when the parent and subsidiary companies were both in federally created insolvency proceedings. In addition to setting an important precedent for the limited ability of federal courts to establish federal common law, the impact of this decision is to allow corporate affiliates to freely decide, in a tax allocation agreement, the beneficiary of a tax refund among a corporate group filing a consolidated tax return, even if the allocation does not align with the company which created the tax losses and even when one or more of the corporate affiliates is in a bankruptcy case or an FDIC receivership. When companies face insolvency, this contractual allocation can be critical to the return available to a particular affiliated company’s creditors, and, in some cases, to lenders who may have taken an assignment of tax refunds.”